The Life of a Data Byte

A byte of data has been stored in a number of different ways as newer, better, and faster mediums of storage are introduced. A byte is a unit of digital information that most commonly refers to eight bits. A bit is a unit of information that can be expressed as 0 or 1, representing logical state.

In the case of paper cards, a bit was stored as the presence or absence of a hole in the card at a specific place. If we go even further back in time to Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a bit was stored as the position of a mechanical gear or lever. For magnetic storage devices, such as tapes and disks, a bit is represented by the polarity of a certain area of the magnetic film. In modern dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), a bit is often represented as two levels of electrical charge stored in a capacitor, a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field.

In June 1956, Werner Buchholz1 coined the word byte2 to refer to a group of bits used to encode a single character of text3. Let’s go over a bit about character encoding. We will start with American Standard Code for Information Interchange, or ASCII. ASCII was based on the English alphabet, therefore every letter, digit, and symbol (a-z, A-Z, 0–9, +, -, /, “, ! etc) were represented as a 7 bit integer between 32 and 127. This wasn’t very friendly to other languages. In order to support other languages, Unicode extended ASCII. With Unicode, each character is represented as a code-point, or character, for example a lower case j is U+006A, where the U stands for Unicode and after that is a hexadecimal number.

UTF-8 is the standard for representing characters as eight bits, allowing every code-point between 0-127 to be stored in a single byte. If we think back to ASCII this is fine for English characters, but other language’s characters are often expressed as two or more bytes. UTF-16 is the standard for representing characters as 16 bits and UTF-32 is the standard for representing characters as 32 bits. In ASCII every character is a byte, and in Unicode, that’s often not true, a character can be 1, 2, 3, or more bytes. Throughout this article there will be different sized groupings of bits. The number of bits in a byte varies based on the design of the storage medium in the past.

This article is going to travel in time through various mediums of storage as an exercise of diving into

how we have stored data through history. By no means will this include every single storage medium ever

manufactured, sold, or distributed. This article is meant to be fun and informative while not being

encyclopedic. Let’s get started. Let’s assume we have a byte of data to be stored: the letter j, or

as an encoded byte 6a or in binary 01001010. As we travel through time, our data byte will come into

play in some of the storage technologies we cover. Finally, the article will

wrap up with a look at the current and future technologies for storage.

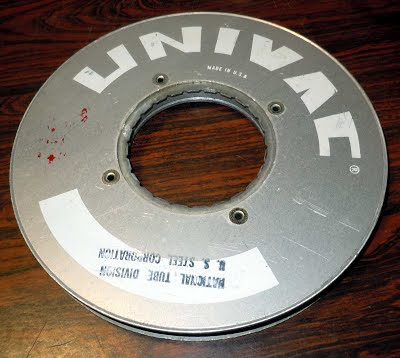

1951

Source for image: http://www.ricomputermuseum.org/Home/interesting_computer_items/univac-magnetic-tape

Our story starts in 1951 with the UNIVAC UNISERVO tape drive for the UNIVAC 1 computer. This was the first tape drive made for a commercial computer. The tape was three pounds of ½ inch wide thin strip of nickel-plated phosphor bronze, called Vicalloy, which was 1,200 feet long. Our data byte could be stored at a rate of 7,200 characters per second4 on tape moving at 100 inches per second. At this point in history, you could measure the speed of a storage algorithm by the distance the tape traveled.

1952

Source for image: https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/storage/storage_PH5-24.html

Let’s fast forward a year to May 21st, 1952 when IBM announced their first magnetic tape unit, the IBM 726. Our data byte could now be moved off UNISERVO metal tape onto IBM’s magnetic tape. This new home would be super cozy for our very small data byte since the tape could store up to 2 million digits. This magnetic 7 track tape moved at 75 inches per second with a transfer rate of 12,500 digits5 or 7,500 characters6 (called copy groups at the time) per second. For reference, this article has 34,128 characters.

7 track tapes had six tracks for data and one to maintain parity by ensuring that the total number of 1-bits in the string was even or odd. Data was recorded at 100 bits per linear inch. This system used a “vacuum channel” method of keeping a loop of tape circulating between two points. This allowed the tape drive to start and stop the tape in a split second. This was done by placing long vacuum columns between the tape reels and the read/write heads to absorb sudden increases in tension in the tape, without which the tape would have typically broken. A removable plastic ring in the back of the tape reel provided write protection. About 1.1 megabytes could be stored on one reel of tape7.

If you think back to VHS tapes, what was required before returning a movie to Blockbuster? Rewinding the tape! The same could be said for tape used for computers. Programs could not hop around a tape, or randomly access data, they had to read and write in sequential order.

1956

Source for image: https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/memory-storage/8/233

If we move ahead a few years to 1956, the era of magnetic disk storage began with IBM’s completion of a RAMAC 305 computer system to deliver to Zellerbach Paper in San Francisco8. This computer was the first to use a moving-head hard disk drive. The RAMAC disk drive consisted of fifty magnetically coated 24 inch diameter metal platters capable of storing about five million characters of data, 7 bits per character, and spinning at 1,200 revolutions per minute. The storage capacity was about 3.75 megabytes.

RAMAC allowed real-time random access memory to large amounts of data, unlike magnetic tape or punch cards. IBM advertised the RAMAC as being able to store the equivalent of 64,000 punched cards9. Previously to the RAMAC, transactions were held until a group of data was accumulated and batch processed. The RAMRAC introduced the concept of continuously processing transactions as they occurred so data could be retrieved immediately when it was fresh. Our data byte could now be accessed in the RAMAC at 100,000 bits per second10. Prior to this, with tapes, we had to write and read sequential data and could not randomly jump to various parts of the tape. Real-time random access of data was truly revolutionary at this time.

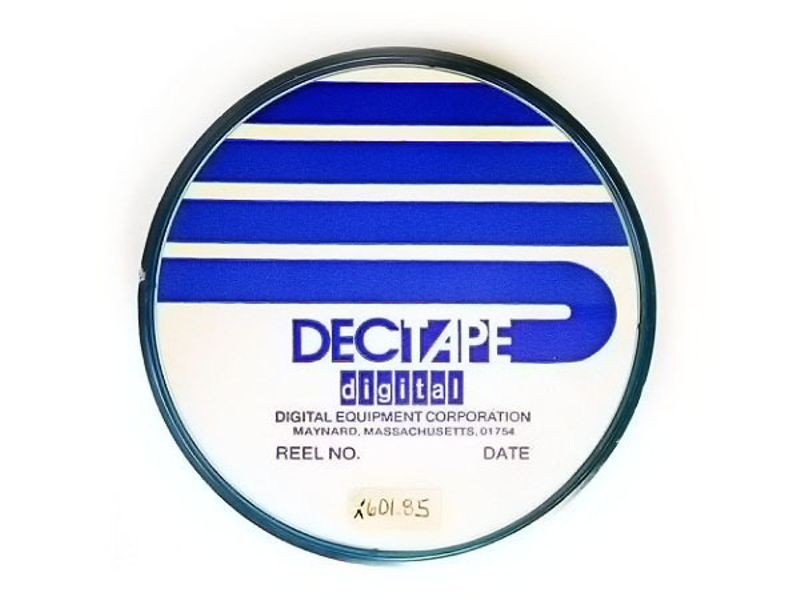

1963

Source for image: https://www.computerhistory.org/timeline/1963/

Let’s fast forward to 1963 when DECtape was introduced. Its namesake stemmed from the Digital Equipment Corporation, known as DEC for short. DECtape was inexpensive and reliable so it was used in many generations of the DEC computers. It was a ¾ inch tape that was laminated and sandwiched between two layers of mylar on a four inch reel.

DECtape could be carried by hand, as opposed to its weighty and large predecessors, making it great for personal computers. In contrast to 7 track tape, DECtape had 6 data tracks, 2 mark tracks, and two clock tracks. Data was recorded at 350 bits per inch. Our data byte, which is 8 bits but could be expanded to 12, could be transferred to DECtape at 8,325 12-bit words per second with a tape speed of 93 +/-12 inches per second11. This is 8% more digits per second than the UNISERVO metal tape in 1952.

1967

Source for image: https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/memory-storage/8/261/1080

Four years later in 1967, a small team at IBM started working on the IBM floppy disk drive, codenamed Minnow12. At the time, the team was tasked with developing a reliable and inexpensive way to load microcode into the IBM System/370 mainframes13. The project then got reassigned and repurposed to load microcode into the controller for the IBM 3330 Direct Access Storage Facility, codenamed Merlin.

Our data byte could now be stored on read-only 8-inch flexible Mylar disks coated with magnetic material, which are today known as floppy disks. At the time of release, the result of the project was named the IBM 23FD Floppy Disk Drive System. The disks could hold 80 kilobytes of data. Unlike hard drives, a user could easily transfer a floppy in its protective jacket from one drive to another. Later in 1973, IBM released a read/write floppy disk drive, which then became an industry standard14.

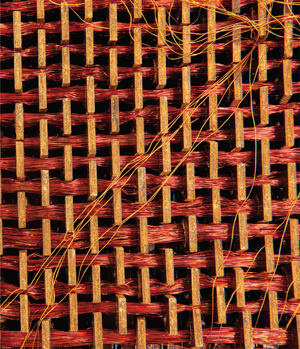

1969

Source for image: https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-history/space-age/software-as-hardware-apollos-rope-memory

In 1969, the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) read-only rope memory was launched into space aboard the Apollo 11 mission, which carried American astronauts to the Moon and back. This rope memory was made by hand and could hold 72 kilobytes of data. Manufacturing rope memory was laborious, slow, and required skills analogous to textile work; it could take months to weave a program into the rope memory15. But it was the right tool for the job at the time to resist the harsh rigors of space. When a wire went through one of the circular cores it represented a 1. Wires that went around a core represented a 0. Our data byte would take a human a few minutes (estimated) to weave into the rope.

1977

Source for image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Commodore-Datasette-C2N-Mk2-Front.jpg

Let’s fast forward to 1977 when the Commodore PET, the first (successful) mass-market personal computer, was released. Built-in to the PET was a Commodore 1530 Datasette, meaning data plus cassette. The PET converted data into analog sound signals that were then stored on cassettes16. This made for a cost-effective and reliable storage solution, albeit very slow. Our small databyte could be transferred at a rate of around 60-70 bytes per second17. The cassettes could hold about 100 kilobytes per 30-minute side, with 2 sides per tape. For example, you could fit about 2 of these 55 KB images18 on one side of the cassette. The datasette also appeared in the Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore 64.

1978

Source for image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRFQm0eUvzs

Let’s jump ahead a year to 1978 when the LaserDisc was introduced as “Discovision” by MCA and Philips. Jaws was the first film sold on a LaserDisc in North America. The audio and video quality on a LaserDisc was far better than the competitors, but too expensive for most consumers. As opposed to the VHS tape which consumers could use to record TV programs, the LaserDisc could not be written to. LaserDiscs used analog video with analog FM stereo sound and pulse-code modulation19, or PCM, digital audio. The disks were 12 inches in diameter and composed of two single sided aluminum disks layered in plastic. The LaserDisc is remembered today as being the foundation CDs and DVDs were built upon.

1979

Source for image: https://www.computerhistory.org/storageengine/seagate-5-25-inch-hdd-becomes-pc-standard/

A year later in 1979, Alan Shugart and Finis Conner founded the company Seagate Technology with the idea of scaling down a hard disk drive to be the same size as a 5 ¼ inch floppy disk, which at the time was the standard. Their first product, in 1980, was the Seagate ST506 hard disk drive, the first hard disk drive for microcomputers. The disk held five megabytes of data, which at the time was five times more than the standard floppy disk. The founders succeeded in their goal of scaling down the drive to the size of a floppy disk drive at 5 ¼ inches. It was a rigid, metallic platter coated on both sides with a thin layer of magnetic material to store data. Our data byte could be transferred at a speed of 625 kilobytes per second20 onto the disk. That’s about a 625KB animated gif21 per second.

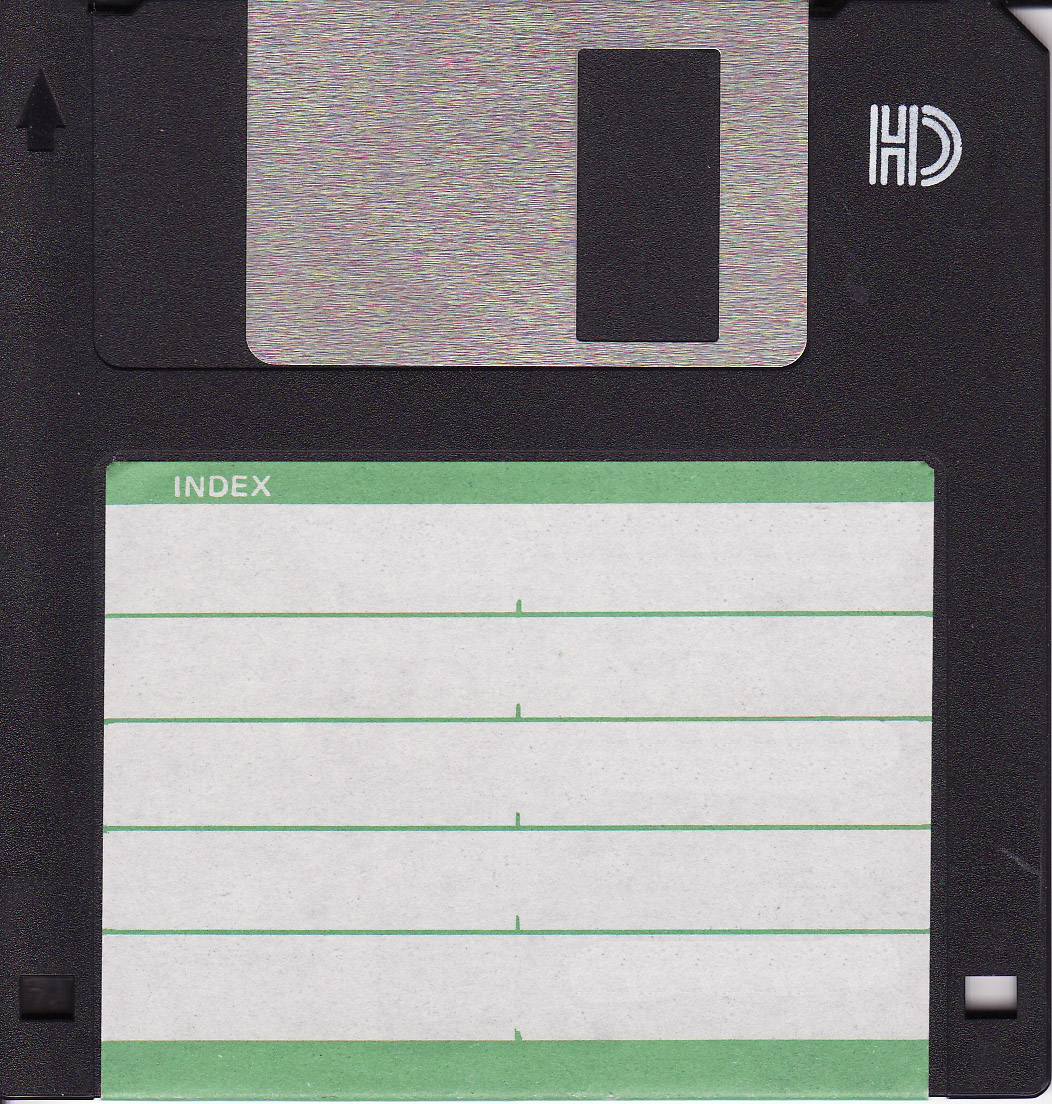

1981

Source for image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_floppy_disk#/media/File:Floppy_disk_300_dpi.jpg

Let’s fast forward a couple years to 1981 when Sony introduced the first 3 ½ inch floppy drives. Hewlett-Packard was the first adopter of the technology in 1982 with their HP-150. This put the 3 ½ inch floppy disk on the map and gave it wide distribution in the industry22. The disks were single sided with a formatted capacity of 161.2 kilobytes and an unformatted capacity of 218.8 kilobytes. In 1982, the double sided version was made available and the Microfloppy Industry Committee (MIC), a consortium of 23 media companies, based a spec for a 3 ½ inch floppy on Sony’s original designs cementing the format into history as we know it23. Our data byte could now be stored on the early version of one of the most widely distributed storage mediums: the 3 ½ inch floppy disk. Later a couple of 3 ½ inch floppy disks holding the contents of The Oregon Trail would be paramount to my childhood.

1984

Source for image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CD-ROM#/media/File:CD-ROM.png

Shortly thereafter in 1984, the compact disk read-only memory (CD-ROM), holding 550 megabytes of pre-recorded data, was announced from Sony and Philips. This format grew out of compact disks digital audio, or CD-DAs, which were used for distributing music. The CD-DA was developed by Sony and Philips in 1982, which has a capacity of 74 minutes. When Sony and Philips were negotiating the standard for a CD-DA, legend has it that one of the four people insisted it be able to hold all of the Ninth Symphony24. The first product released on a CD-ROM was Grolier’s Electronic Encyclopedia, which came out in 1985. The encyclopedia contained nine million words which only took up 12% of the disk space available, which was 553 mebibytes25. We would have more than enough room for the encyclopedia and our data byte. Shortly thereafter in 1985, computer and electronics companies worked together to create a standard for the disks so any computer would be able to access the information.

1984

In 1984, Fujio Masuoka invented a new type of floating-gate memory, called flash memory, that was capable of being erased and reprogrammed multiple times.

Let’s go over a bit about floating-gate memory. Transistors are electrical gates that can be switched on and off individually. Since each transistor can be in two distinct states (on or off), it can store two different numbers: 0 and 1. Floating-gate refers to the second gate added to the middle transistor. This second gate is insulated by a thin oxide layer. These transistors use a small voltage, applied to the gate of the transistor, to denote whether it is on or off, which in turn translates to a 0 or 1.

With a floating gate, when a suitable voltage is applied across the oxide layer, the electrons

tunnel through it and get stuck on the floating gate. Therefore even if the power is disconnected,

the electrons remain present on the floating gate. When no electrons are on the floating gate it

represents a 1, and when electrons are trapped on the floating gate it represents a 0. Reversing

this process and applying a suitable voltage across the oxide layer in the opposite direction

causes the electrons to tunnel off the floating gate and restore the transistor back to its

original state. Therefore, the cells are made programmable and non-volatile26. Our data byte

could be programmed into the transistors as 01001010, with electrons trapped in the floating

gates to represent the zeros.

Masuoka’s design was a bit more affordable but less flexible than electrically erasable PROM (EEPROM) since it required multiple groups of cells to be erased together, but this also accounted for its speed. At the time, Masuoka was working for Toshiba. He ended up quitting Toshiba shortly after to become a professor at Tohoku University because he was displeased with the company not rewarding him for his work. He sued Toshiba, demanding compensation for his work, which settled in 2006 with a one-time payment of ¥87m, equivalent to $758,000. This still seems light given how impactful flash memory has been on the industry.

While we are on the topic of flash memory, we might as well cover the difference between NOR and NAND flash. We know by now from Masuoka that flash stores information in memory cells made up of floating gate transistors. The names of the technologies are tied directly to the way the memory cells are organized.

In NOR flash, individual memory cells are connected in parallel allowing the random access. This architecture enables the short read times required for the random access of microprocessor instructions. NOR Flash is ideal for lower-density applications that are mostly read only. This is why most CPUs load their firmware, typically, from NOR flash. Masuoka and colleagues presented the invention of NOR flash in 1984 and NAND flash in 198727.

In contrast, NAND Flash designers gave up the ability for random access in a tradeoff to gain a smaller memory cell size. This also has the benefits of a smaller chip size and lower cost-per-bit. NAND flash’s architecture consists of an array of eight memory transistors connected in a series. This leads to high storage density, smaller memory cell size, and faster write and erase since it can program blocks of data at a time. This comes at the cost of having to overwrite data when it is not sequentially written and data already exists in a block28.

1991

Let’s jump ahead to 1991 when a prototype solid state disk (SSD) module was made for evaluation by IBM from SanDisk, at the time known as SunDisk29. This design combined a flash storage array, non-volatile memory chips, with an intelligent controller to automatically detect and correct defective cells. The disk was 20 megabytes in a 2 ½ inch form factor and sold for around $1,00030. This wound up being used by IBM in the ThinkPad pen computer31.

1994

Source for image: https://www.amazon.com/Iomega-100MB-Zip-Plus-Drive/dp/B003UI8POM

One of my personal favorite storage mediums from my childhood was Zip Disks. In 1994, Iomega released the Zip Disk, a 100 megabyte cartridge in a 3 ½ inch form factor, roughly a bit thicker than a standard 3 ½ inch disk. Later versions of the disks could store up to 2 gigabytes. These disks had the convenience of being as small as a floppy disk but with the ability to hold a larger amount of data, which made them compelling. Our data byte could be written onto a Zip disk at 1.4 megabytes per second. At the time, a 1.44 megabyte 3 ½ inch floppy would write at about 16 kilobytes per second. In a Zip drive, heads are non-contact read/write and fly above the surface, which is similar to a hard drive but unlike other floppies. Due to reliability problems and the affordability of CDs, Zip disks eventually became obsolete.

1994

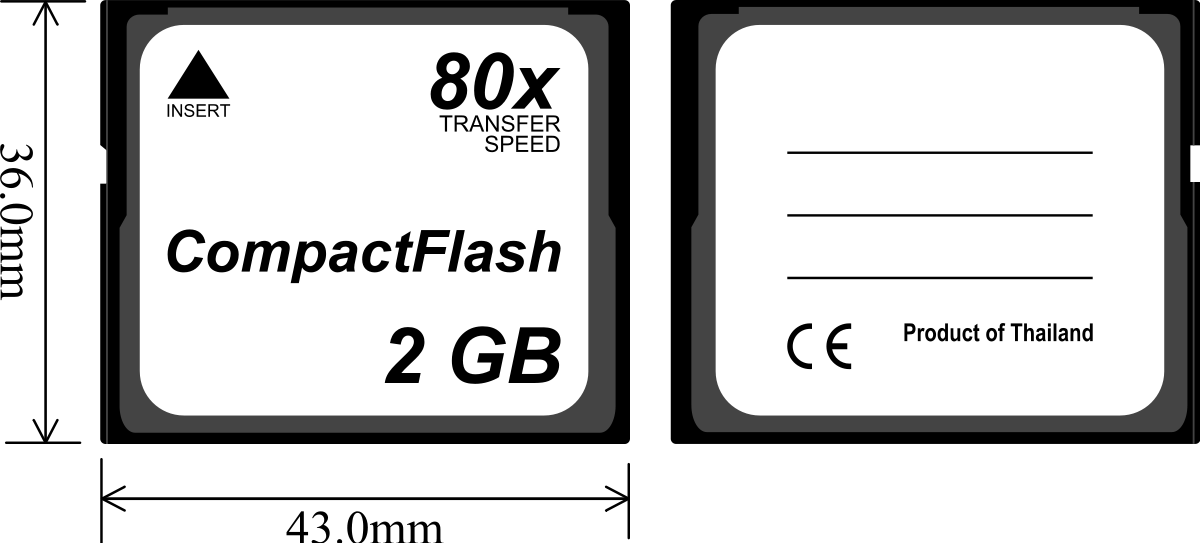

Source for image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CompactFlash#/media/File:CompactFlash_Memory_Card.svg

Also in 1994, SanDisk introduced CompactFlash, which was widely adopted into consumer devices like digital and video cameras. Like CD-ROMs, CompactFlash speed is based on “x”-ratings, such as 8x, 20x, 133x, etc. The maximum transfer rate is calculated based on the original audio CD transfer rate of 150 kilobytes per second. This winds up looking like R = K ⨉ 150 kB/s, where R is the transfer rate and K is the speed rating. So for 133x CompactFlash, our data byte would be written at 133 ⨉ 150 kB/s or around 19,950 kB/s or 19.95 MB/s. The CompactFlash Association was founded in 1995 to create an industry standard for flash-based memory cards32.

1997

A few years later in 1997, the compact disc rewritable (CD-RW) was introduced. This optical disc was used for data storage, as well as backing up and transferring files to various devices. CD-RWs can only be rewritten about 1,000 times, which, at the time, was not a limiting factor since users rarely overwrote data that often on one disc.

CD-RWs are based on phase change technology. During a phase change of a given medium, certain

properties of the medium change. In the case of CD-RWs, phase shifts in a special compound,

composed of silver, tellurium, and indium, cause “reflecting lands” and “non-reflecting bumps”,

each representing a 0 or 1. When the compound is in a crystalline state, it is translucent,

which indicates a 1. When the compound is melted into an amorphous state, it becomes opaque and

non-reflective, which indicates a 033. We could write our data byte 01001010 as “non-reflecting bumps”

and “reflecting lands” this way.

DVDs eventually overtook much of the market share from CD-RWs.

1999

Let’s fast forward to 1999, when IBM introduced the smallest hard drives in the world at the time: the IBM microdrive in 170 MB and 340 MB capacities. These were small hard disks, 1 inch in size, designed to fit into CompactFlash Type II slots. The intent was to create a device to be used like CompactFlash but with more storage capacity. However, these were soon replaced by USB flash drives, covered next, and larger CompactFlash cards once they became available. Like other hard drives, microdrives were mechanical and contained small, spinning disk platters.

2000

A year later in 2000, USB flash drives were introduced. These drives consisted of flash memory encased in a small form factor with a USB interface. Depending on the version of the USB interface used the speed varies. USB 1.1 is limited to 1.5 megabits per second, whereas USB 2.0 can handle 35 megabits per second, and USB 3.0 can handle 625 megabits per second34. The first USB 3.1 type-C drives were announced in March 2015 and had read/write speeds of 530 megabits per second35. Unlike floppy and optical disks, USB devices are harder to scratch but still deliver the same use cases of data storage and transferring and backing up files. Because of this, drives for floppy and optical disks have since faded out of existence in favor of USB ports.

2005

Source for image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_disk_drive#/media/File:Laptop-hard-drive-exposed.jpg

In 2005, hard disk drive (HDD) manufacturers started shipping products using perpendicular magnetic recording, or PMR. Quite interestingly, this happened at the same time the iPod Nano announced using flash as opposed to the 1 inch hard drives in the iPod Mini, causing a bit of an industry hoohaw36.

A typical hard drive contains one or more rigid disks coated with a magnetically sensitive film consisting of tiny magnetic grains. Data is recorded when a magnetic write-head flies just above the spinning disk, much like a record player and a record except a record needle is in physical contact with the record. As the platters spin, the air in contact with them creates a slight breeze. Just like air on an airplane wing generates lift, the air generates lift on the head’s airfoil37. The write-head rapidly flips the magnetization of one magnetic region of grains so that its magnetic pole points up or down, to denote a 1 or a 0.

The predecessor to PMR was longitudinal magnetic recording, or LMR. PMR can deliver more than three times the storage density of LMR. The key difference of PMR versus LMR is that the grain structure and the magnetic orientation of the stored data of PMR media is columnar instead of longitudinal. PMR has better thermal stability and improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to better grain separation and uniformity. It also benefits from better writability due to stronger head fields and better magnetic alignment of the media. Like LMR, PMR’s fundamental limitations are based on the thermal stability of magnetically written bits of data and the need to have sufficient SNR to read back written information.

2007

Let’s jump ahead to 2007, when the first 1 TB hard disk drive from Hitachi Global Storage Technologies was announced. The Hitachi Deskstar 7K1000 used five 3.5 inch 200 gigabytes platters and rotated at 7,200 RPM. This is in stark contrast to the world’s first HDD, the IBM RAMAC 350, which had a storage capacity that was approximately 3.75 megabytes. Oh how far we have come in 51 years! But wait, there’s more.

2009

In 2009, technical work was beginning on non-volatile memory express, or NVMe38. Non-volatile memory

(NVM) is a type of memory that has persistence, in contrast to volatile memory which needs constant

power to retain data. NVMe filled a need for a scalable host controller interface for peripheral

component interconnect express (PCIe) based solid state drives39, hence the name NVMe. Over 90 companies

were a part of the working group to develop the design. This was all based on prior work to define the

non-volatile memory host controller interface specification (NVMHCIS). Opening up a modern server would

likely result in finding some NVMe drives. The best NVMe drives today can do about 3,500 megabytes per

second read and 3,300 megabytes per second write40. For the data byte we started with, the character j,

that is extremely fast compared to a couple of minutes to hand weave rope memory for the Apollo Guidance Computer.

Today and the future

Storage class memory (SCM)

Now that we have traveled through time a bit (ha!), let’s take a look at the state of the art for storage class memory (SCM) today. SCM, like NVM, is persistent, but SCM goes further by also providing performance better than or comparable to primary memory as well as byte addressability41. SCM aims to address some of the problems faced by caches today such as the low density of static random access memory (SRAM). With dynamic random access memory (DRAM)42, we can get better density, but this comes at a cost of slower access times. DRAM also suffers from requiring constant power to refresh memory. Let’s break this down a bit. Power is required since the electric charge on the capacitors leaks off little by little, meaning without intervention, the data on the chip would soon be lost. To prevent this leakage, DRAM requires an external memory refresh circuit which periodically rewrites the data in the capacitors, restoring them to their original charge.

To solve the problems with density and power leakage, there are a few SCM technologies developing: phase change memory (PCM), spin-transfer torque random access memory (STT-RAM), and resistive random access memory (ReRAM). One thing that is nice about all these technologies is their ability to function as multi-level cells, or MLCs. This means they can store more than one bit of information, compared to single-level cells (SLCs) which can store only one bit per memory cell, or element. Typically, a memory cell consists of one metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET). MLCs reduce the number of MOSFETs required to store the same amount of data as SLCs, making them more dense or smaller to deliver the same amount of storage as technologies using SLCs. Let’s go over how each of these SCM technologies work.

Phase change memory (PCM)

Earlier we went over how phase change works for CD-RWs. PCM is similar. It’s phase change material is typically Ge-Sb-Te, also known as GST, which can exist in two different states: amorphous and crystalline. The amorphous state has a higher resistance, denoting a 0, than the crystalline state denoting a 1. By assigning data values to intermediate resistances, PCM can be used to store multiple states as a MLC43.

Spin-transfer torque random access memory (STT-RAM)

STT-RAM consists of two ferromagnetic, permanent magnetic, layers separated by a dielectric, meaning an insulator that can transmit electric force without conduction. It stores bits of data based on differences in magnetic directions. One magnetic layer, called the reference layer, has a fixed magnetic direction while the other magnetic layer, called the free layer, has a magnetic direction that is controlled by passing current. For a 1, the magnetization direction of the two layers are aligned. For a 0, the two layers have opposing magnetic directions.

Resistive random access memory (ReRAM)

A ReRAM cell consists of two metal electrodes separated by a metal oxide layer. We can think of this as slightly similar to Masuoka’s original flash memory design, where electrons would tunnel through the oxide layer and get stuck in the floating gate or vice-versa. However, with ReRAM, the state of the cell is determined based on the concentration of oxygen vacancy in the metal oxide layer.

While these technologies are promising, they still have downsides. PCM and STT-RAM have high write latencies. PCMs latencies are ten times that of DRAM, while STT-RAM has ten times the latencies of SRAM. PCM and ReRAM have a limit on write endurance before a hard error occurs, meaning a memory element gets stuck at a particular value44.

In August 2015, Intel announced Optane, their product build on 3DXPoint, pronounced 3D cross-point45. Optane claims performance 1,000 faster than NAND SSDs with 1,000 times the performance, while being four to five times the price of flash memory. Optane is proof that storage class memory is not just experimental. It will be interesting to watch how these technologies evolve.

Hard disk drives (HDDs)

Helium hard disk drive (HHDD)

A helium drive is a high capacity hard disk drive (HDD) that is helium-filled and hermetically sealed during manufacturing. Like other hard disks, as we covered earlier, it looks much like a record player with a magnetic-coated platter rotating. Typical hard disk drives would just have air inside the cavity, however that air is causing an amount of drag on the spin of the platters.

Helium balloons float so we know helium is lighter than air. Helium is, in fact, 1/7th the density of air, therefore reducing the amount of drag on the spin of the platters, causing a reduction in the amount of energy required for the disks to spin. However, this was actually a secondary feature, the primary feature of helium was to allow for packing 7 platters in the same form factor that would typically only hold 5. When trying to attempt this with air filled drives, it would cause turbulence. If we remember back to our airplane wing analogy from earlier this ties in perfectly. Since helium reduces drag, this eliminates the turbulence.

What we also know about balloons is that after a few days, helium filled balloons start to sink because helium is escaping the balloons. The same could be said for these drives. It took years before manufacturers had created a container that prevented the helium from escaping the form factor for the life of the drive. Backblaze experimented and found that while helium hard drives had a lower annualized error rate of 1.03%, while standard hard drives resulted in 1.06%. Of course, that is so small a difference it is hard to conclude much from it46.

A helium filled form factor can have a hard disk drive encapsulated that uses PMR, which we went over above, or could contain a microwave-assisted magnetic recording (MAMR) or heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) drive. You can pair any magnetic storage technology with helium instead of air. In 2014, HGST combined two cutting edge technologies into their 10TB helium hard disk that used host-managed shingled magnetic recording, or SMR. Let’s go over a bit about SMR then we can cover MAMR and HAMR.

Shingled magnetic recording (SMR)

We went over perpendicular magnetic recording (PMR) earlier which was SMR’s predecessor. In contrast to PMR, SMR writes new tracks that overlap part of the previously written magnetic track, which in turn makes the previous track narrower, allowing for higher track density. The technology’s namesake stems from the fact that the overlapping tracks are much like that of roof shingles.

SMR results in a much more complex writing process since writing to one track winds up overwriting an adjacent track. This doesn’t come into play when a disk platter is empty and data is sequential. But once you are writing to a series of tracks that already contain data, this process is destructive to existing adjacent data. If an adjacent track contains valid data it must be rewritten. This is quite similar to NAND flash as we covered earlier.

Device-managed SMR devices hide this complexity by having the device firmware manage it resulting in an interface like any other hard disk you might encounter. On the other hand, host-managed SMR devices rely on the operating system to know how to handle the complexity of the drive.

Seagate started shipping SMR drives in 2013 claiming a 25% greater density than PMR47.

Microwave-assisted magnetic recording (MAMR)

MAMR is an energy-assisted magnetic storage technology, like HAMR which we will cover next, that uses 20-40GHz frequencies to bombard the disk platter with a circular microwave field, lowering the its coercivity, meaning the platter has a lower resistance of its magnetic material to changes in magnetization. We learned above that changes in magnetization of a region of the platter are used to denote a 0 or a 1 so this allows the data to be written much more densely on the disk since it has a lower resistance to changes in magnetization. The core of this new technology is the spin torque oscillator used to generate the microwave field without sacrificing reliability.

Western Digital, also known as WD, unveiled this technology in 201748. Toshiba followed shortly after in 201849. While WD and Toshiba are busy pursuing MAMR, Seagate is betting on HAMR.

Heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR)

HAMR is an energy-assisted magnetic storage technology for greatly increasing the amount of data that can be stored on a magnetic device, such as a hard disk drive, by using heat delivered by a laser to help write data onto the surface of a hard disk platter. The heat causes the data bits to be much closer together on the disk platter, which allows greater data density and capacity.

This technology is quite difficult to achieve. A 200mW laser heats a teeny area of the region to 750 °F (400 °C) quickly before writing the data, while also not interfering with or corrupting the rest of the data on the disk50. The process of heating, writing the data, and cooling must be completed in less than a nanosecond. These challenges required the development of nano-scale surface plasmons, also known as a surface guided laser, instead of direct laser-based heating, as well as new types of glass platters and heat-control coatings to tolerate rapid spot-heating without damaging the recording head or any nearby data, and various other technical challenges that needed to be overcome51.

Seagate first demonstrated this technology, despite many skeptics, in 201352. They started shipping the first drives in 201853.

End of tape, rewind

We started this article in 1951 and are concluding after looking at the future of storage technology. Storage has changed a lot over time, from paper tape, to metal tape, magnetic tape, rope memory, spinning disks, optical disks, flash, and others. Progress has led to faster, smaller, and more performant devices for storing data.

If we compare NVMe to the 1951 UNISERVO metal tape, NVMe can read 486,111% more digits per second. If we compare NVMe to my childhood favorite in 1994, Zip disks, NVMe can read 213,623% more digits per second.

One thing that remains true is the storing of 0s and 1s. The means by which we do that vary greatly. I hope the next time you burn a CD-RW with a mix of songs for a friend, or store home videos in an Optical Disc Archive54, you think about how the non-reflective bumps translate to a 0 and the reflective lands of the disk translate to a 1. Or if you are creating a mixtape on a cassette, remember that those are very closely related to the Datasette used in the Commodore PET. Lastly, remember to be kind and rewind55.

Thank you to Robert Mustacchi and Rick Altherr for tidbits (I can’t help myself) throughout this article!

- http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/IBM/Stretch/pdfs/06-07/102632284.pdf [return]

- https://archive.org/stream/byte-magazine-1977-02/1977_02_BYTE_02-02_Usable_Systems#page/n145/mode/2up [return]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170403130829/http://www.bobbemer.com/BYTE.HTM [return]

- https://www.computerhistory.org/storageengine/tape-unit-developed-for-data-storage/ [return]

- https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/701/701_1415bx26.html [return]

- https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/storage/storage_fifty.html [return]

- https://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/hardware/why-the-future-of-data-storage-is-still-magnetic-tape [return]

- https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/650/650_pr2.html [return]

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOD1umMX2s8 [return]

- https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/ramac/ [return]

- https://www.pdp8.net/tu56/tu56.shtml [return]

- https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/floppy/ [return]

- https://archive.org/details/ibms360early370s0000pugh/page/513 [return]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100707221048/http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/Oral_History/102657926.05.01.acc.pdf [return]

- https://authors.library.caltech.edu/5456/1/hrst.mit.edu/hrs/apollo/public/visual3.htm [return]

- http://wav-prg.sourceforge.net/tape.html [return]

- https://www.c64-wiki.com/wiki/Datassette [return]

- You will be rick rolled by a still photo. [return]

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4856#page-17 [return]

- https://www.pcmag.com/encyclopedia/term/st506#:~:text=ST506,using%20the%20MFM%20encoding%20method. [return]

- You will be rick rolled. [return]

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/24530873?seq=1 [return]

- https://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Consumer/Archive-Byte-IDX/IDX/80s/82-83/Byte-1983-09-OCR-Page-0169.pdf [return]

- https://www.wired.com/2010/12/1216beethoven-birthday-cd-length/ [return]

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RTwQAQAAMAAJ [return]

- https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2006/03/11/not-just-a-flash-in-the-pan [return]

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1487443 [return]

- http://aturing.umcs.maine.edu/~meadow/courses/cos335/Toshiba%20NAND_vs_NOR_Flash_Memory_Technology_Overviewt.pdf [return]

- https://www.computerhistory.org/storageengine/solid-state-drive-module-demonstrated/ [return]

- http://meseec.ce.rit.edu/551-projects/spring2017/2-6.pdf [return]

- https://www.westerndigital.com/company/innovations/history [return]

- https://www.compactflash.org/ [return]

- https://computer.howstuffworks.com/cd-burner8.htm [return]

- https://www.diffen.com/difference/USB_1.0_vs_USB_2.0 [return]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20161220102924/http://www.usb.org/developers/presentations/USB_DevDays_Hong_Kong_2016_-_USB_Type-C.pdf [return]

- https://www.eetimes.com/hard-drives-go-perpendicular/# [return]

- https://books.google.com/books?id=S90OaKQ-IzMC&pg=PA590&lpg=PA590&dq=heads+disk+airfoils&source=bl&ots=7VVuhw6mgm&sig=ACfU3U0PXCehcs7dKI5IhDGbRMZvqsgeHg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi82fm9_onoAhUIr54KHR6-BtUQ6AEwAHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=heads%20disk%20airfoils&f=false [return]

- https://www.flashmemorysummit.com/English/Collaterals/Proceedings/2013/20130813_A12_Onufryk.pdf [return]

- https://nvmexpress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/NVM_whitepaper.pdf [return]

- https://www.pcgamer.com/best-nvme-ssd/ [return]

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5388605 [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.12221.pdf [return]

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5388621 [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.12221.pdf [return]

- https://www.anandtech.com/show/9541/intel-announces-optane-storage-brand-for-3d-xpoint-products [return]

- https://www.backblaze.com/blog/helium-filled-hard-drive-failure-rates/ [return]

- https://www.anandtech.com/show/7290/seagate-to-ship-5tb-hdd-in-2014-using-shingled-magnetic-recording/ [return]

- https://www.storagereview.com/news/wd-unveils-its-microwave-assisted-magnetic-recording-technology [return]

- https://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/12/07/toshiba_goes_to_mamr/ [return]

- https://fstoppers.com/originals/hamr-and-mamr-technologies-will-unlock-hard-drive-capacity-year-326328 [return]

- https://www.seagate.com/www-content/ti-dm/tech-insights/en-us/docs/TP707-1-1712US_HAMR.pdf [return]

- https://www.computerworld.com/article/2485341/seagate--tdk-show-off-hamr-to-jam-more-data-into-hard-drives.html [return]

- https://blog.seagate.com/craftsman-ship/hamr-next-leap-forward-now/ [return]

- Yup, you heard that right: https://pro.sony/en_GB/products/optical-disc. [return]

- This is a tribute to Blockbuster but there are still open formats for using tape today: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear_Tape-Open. [return]